Hip Internal Rotation & Better Squats- Is There Really a Correlation?

Over the past 10 years hip internal rotation has become a bit over hyped in the fitness and rehab world. I believe though hip internal rotation is no more important than any other range of motion in the body, it certainly has its reasons to be trained.

Recently I’ve seen arguments on whether training hip internal rotation in an attempt to improve your squat is actually worthwhile. I am a bit sick of blanket statements being made in order to get attention so I figured I would vent to you all and explain my thoughts.

First we need to define “better squat.” This is where individual goals matter the most. Is there pain associated with the squat? Do you want to just build a stronger squat? Want jacked legs? Are you interested in a deeper resting squat? Context matters most!

Strength

First, let’s address performance or increased strength in a back squat. In this case, increasing hip IR and back squat 1RM are completely separate and opposing goals. I am not even sure why this is an argument. You can squat with hip IR limitations as long as you optimize your stance width to suit your anatomy. Some of the most explosive and powerful athletes have limited hip IR as an adaptive by-product of their sport/ movement demands.

The more range in the hip means it changes the moment arms, which alters joint torque for the same muscle force. Longer moment arms means there is less muscle force needed to produce the same torque. In simpler terms- Less weight will feel more challenging the deeper you go in a squat. So if all you care about is increasing maximum strength, than you basically only want enough range of motion in your joint to complete the required task. Nothing more. This is why most powerlifters can only squat to parallel or just below and have almost no hip internal rotation. Squatting past parallel is where hip IR mobility becomes important. For the sport of powerlifting, as long as the hip crease is just below the top of the knee, it’s a green light.

Now if you are an olympic weightlifter, you need that deeper squat. We see all the time when an athlete is buried deep in the bottom of a heavy snatch or clean, they use IR to their advantage. If you want to get your butt to the floor, that requires the hip to internally rotate to a degree. However, there are some weightlifters that are bigger and more muscular with less IR and you see them keep their knees out at the bottom. So there are certainly work arounds- which we will touch on later.

Essentially, if the task requires deep squat ranges then you should probably be comfortable in a deep squat and invest training time into specific and isolated mobility work. If you have enough mobility for the sport or task you enjoy, then don’t invest time in mobility that you’ll never use anyways.

Sonny Webster showcasing IR in the bottom of a snatch

Squat Biomechanics

Is an adequate amount of hip IR needed to squat efficiently in the first place, or can you get by just fine without it?

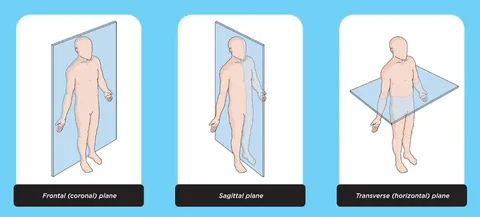

The truth is, the squat is a compound movement where multiple joints organize themselves in a way to complete the task- moving a weight down and back up. The squat is a SAGITTAL plane movement meaning the load is moving through flexion and extension. Hip internal rotation is a function of the TRANSVERSE plane. Therefore, they are not directly correlated.

If we want to load the hip extensors at length in an ass to grass squat we need to be able to flex the hip first and foremost. The hip extensors that are most active coming out of the bottom of the squat are primarily the adductor magnus and glute max. These muscles need to have the flexibility to achieve the necessary hip flexion in a deep squat. The frontal (side to side) and transverse (rotational) planes really aren’t loaded at all in a squat.

Typically, reductions in hip flexion will lead to a wider stance and foot turn out to create space to bring the knee to chest. So technically if you find an appropriate stance width and you have decent extensibility of the hip extensors you can get away with a perfectly deep squat without even worrying about the amount the hip can rotate. The reason we turn our feet out and widen our stance is to create the space for IR to occur. Internal rotation in inevitable when you reach your max hip flexion whether you have to start from more external rotation or keep a more narrow stance in the sagittal plane.

If you struggle with excessive foot turn out, then I HIGHLY suggest you watch this video I created HERE. I cover the main reasons why the foot turns out in gait and squatting and 5 exercises to help fix It. (If you think it needs fixing)

Hip Flexion/IR Biomechanics

Like I mentioned, reduced hip flexion will cause compensations to occur. This will either be foot turn out, stance width increases, or the lumbar spine tucking under (butt wink) when you run out of hip space. If you cannot achieve a genuine 90 degrees of hip flexion then most likely you will have reduced space in the hip in all other planes. This is because the adductors and glutes function in all 3 planes and improving range of motion in each direction will slacken the muscle when it reaches end range in another plane. This means if you have reduced hip flexion, then perhaps improving hip rotation can slacken the muscles responsible for restricting hip flexion. But this depends on the individual. Also if you want to be able to achieve a clean 120 degrees of hip flexion without the knee tracking outward and foot turning in, the this requires the femur to internally rotate relative to the pelvis to stay in line.

So I do think having some amount of internal rotation is important for more movement options related to the squat. Most people just interested in fitness and more functional use of their lower body will want to be able to squat in multiple ways- wide/narrow stance, single leg squats (pistols,dragons), w- squats, butterfly squats, etc. Life is more fun with more movement options in my opinion. If you are a powerlifter, or a professional athlete looking to only run fast and jump high, then you really don’t need to prioritize flexibility goals in general.

Hip Pain

If you are are very limited in hip IR, then it can be worth trying to improve it to increase the variability at pelvis and femur to help spread and distribute force across a broader surface area of tissue. Since we see an association with lack of hip IR and osteoarthritis, femoroacetabular impingement, and tendinopathies people automatically assume those conditions stem from a lack of hip IR. Sometimes it can be the other way around and the lack of IR can be a result of the nervous system guarding that range due to pain. It is very common when squatting to get anterior hip pain when the femur gets to around 90 degrees of flexion. People tend to jump straight to addressing hip IR, but there are many other factors at play on why anterior hip tissues become aggravated.

If the pelvis is “stuck” in an anterior orientation, then this drags the femur in to internal rotation along with it. Meaning when the pelvis tips forward it reduces the space to internally rotate. The hip socket will sit more in front and below the femoral head. This means the femoral neck is more closely aligned with the anterior rim of the acetabulum. When you internally rotate you will just hit the anterior rim earlier which can end up becoming sensitive over time. So before you go forcing more Internal rotation in an already painful hip, you should probably make sure you create the space at the pelvis first. Particularly, we would look at the ability for the pelvis to rotate posteriorly relative to the femur. This will provide more clearance for the femur to flex and Internally rotate. But once sensitivity starts to decrease, we should be able to flex the femur and pelvis simultaneously which will demonstrate true hip flexion capabilities.

J. Bagwell, et al., 2016.

However range of motion deficits are just one side of the coin when it comes to joint pain. We have to consider the kinetic measures and how they influence range of motion at a joint. If the muscles that cross a joint cannot handle forces based on the tasks that take the joint through full range of motion, then that may manifest as constant muscle guarding around the joint. In this case, reduced hip IR when assessed cold can also be a muscle power deficit issue, not necessarily a capsular mobility issue. I have actually seen this quite often when assessing new clients who always feel “stiff” but when they warm up rotational range of motion is wildly better. We have to consider the kinematic (overall ROM/space) and kinetic (muscular) forces that act on the hip joint. The deep hip external rotators may not function well at length, the iliopsoas complex may be undertrained, the adductors may be weaker in one plane vs others for example. There are many muscles that cross the hip that can contribute to a lack of hip rotation simply because the nervous system is shutting down the mobility of the joint as a means of increasing stability since the muscles can’t create it. Therefore, overuse injuries and pain are typically a combo of both but of course it always context and person specific.

Load management is the most important concept to consider when navigating pain and injury rehab. Actually, increasing mobility can be a form of load management. See this post on the subject HERE.

Increased variability and movement options can be obtained by 1) increasing space to move, 2) increasing strength/ capacity to handle the demands of a given task & 3) coordinating motor abilities to share workload amongst neighboring joints so one doesn’t take the majority of the stress. In a rehab scenario, load management is about managing external physiological stressors intended to promote recovery and positive adaptation. Though low intensity mobility work is just one way to desensitize painful joints, it can be used as a way to change the way you move, thus offloading overused tissues that's aren't recovering well.

Where people go wrong in the context of hip pain is forcing mobility training on a flared up hip. If hip IR is restricted due to pain, then you need to let inflammation settle down before trying to expand that range. Of course flirting with the pain is a necessary form of rehab but sometimes you need to let an area heal while focusing on improving flexibility in non painful ranges first. Hip rotational flexibility work is taxing on the joint when trained correctly. Save the intensity for when there is less apprehension through internal rotation to get the most out of it.

W- Sit Training for Hip IR

Flexibility/Mobility

If increasing hip flexion can increase hip IR, then why can’t it be the other way around. I find in instances where hip flexion is painful, but internal rotation exercises are limited but NOT painful, then working internal rotation can be extremely helpful for improving flexion.

At the end of the day, it’s all related. Improving hip IR has it’s benefits, but its also not special. What’s important is addressing the client/ athlete’s unique limitations relative to the goal at hand.

Many people come to me with the goal of improving their squat mobility and achieving a comfortable resting or loaded squat. If mobility is the goal, then 100% we are looking at prioritizing hip rotation to increase the space within the hip.

Working on hip Internal rotation and external rotation made my squat much more comfortable. But to be honest, I needed to free up my more superficial muscles (hip flexors, adductors) first before I could really make progress in hip IR- most likely due to Inability to flex and posteriorly tilt the pelvis.

Since Hip IR is a component of hip flexion based on the arthrokinematics, then any movement requiring hip flexion or anterior pelvic tilt would benefit from increaed hip IR when it comes to improving the flexibility of that position. Whether that is a squat, an RDL, forward fold, or even the splits.

Just like deep squats, I have seen those with very limited hip IR achieve a middle split. However the ones who can display their split cold with little to no resistance typically have a decent amount of hip IR in my experience.

If your main goal is to get flexible then hip rotation is very important. I wouldn’t put a specific number on how much internal or external rotation you need, But I always reccommend a rotatioal arch of at least 75-100 degrees. Ideally you don’t want all of that rotation coming from internal or external rotation alone, but an even mix with a slight bias to one is totally fine. Greater degrees of external rotation is a more realistic metric- somewhere between 50-90degrees, while internal rotation we are looking at 25-45 as a goal. So you don’t need a ton of IR, but having some of it goes a long way.

Remember- just training hip rotation will not give you a split, or deeper forward fold/ squat alone. I see it more as a way of creating space and comfort within the hip joint so the nervous system senses as little apprehension and resistance as possible when training the main positions in order to load the target muscles adequately. For example- there are many people who feel jamming in the hip joint before feeling the adductors stretch in their middle split. Improving some hip rotation (In whatever direction is limited) can help access a bit more anterior pelvic tilt and reduce crowding of the femur on the rim of the acetabulum.

You can understand more about the biomechanics behind Hip Internal Rotation and Hip Flexion with this video HERE

Table Tests vs Loaded Test

There is a lot of criticism on passive, isolated range of motion testing on whether it is relevant to a clients goals or limitations. The main criticism is that the body self organizes differently under load vs at rest. For example, there are weightlifters who struggle to squat ass to grass with a pvc pipe but when they load up 225lb on their back they have a perfect looking squat.

Here’s the thing, its normal for added load to assist range of the motion… I mean thats the basis for loaded progressive stretching that we use to build flexibility. The question is how much load do we need to access that ROM?

Most people that come to a physiotherapist for help have complaints of every day movements bothering them. Picking things up off the ground, touching their toes, sitting cross legged, etc. They dont need help getting into range with added load, they want to be able to access a decent range of motion without a warm up, and extra weight assistance.

Passive tests won’t be a definitive assessment for how someones loaded squat would look. Loaded issues like a hip shift or pain under high loads require loaded assessments. But passive assessments will help you understand how someone navigates life and day to day tasks. They are both helpful in my opinion because seeing the difference in range of motion between the two can really clue you in to what the client needs.

You may see someone with 5 degrees of hip IR in a passive table test, but can still squat ass to grass with 80% of their 1 RM. That is fine, but it doesn’t mean the athlete won’t benefit from improving those passive table measures especially if they are interested in more flexibility, or less resting tone when they are not training.

Joint capsule restrictions aren’t always so obvious to the everyday active person compared to more superficial muscles. Tight hamstring are obvious because we need to bend over and touch our toes daily. But this is why a physio or a coach who understands biomechanics and mobility can help a client make sense of whether rotational restrictions at the joint level can be contributing to some of their flexibility limitations they are experiencing. The key is not getting lost in thinking improving hip IR is going to make that toe touch better on its own. You’d still need to train those hamstrings in their lengthened position but perhaps if the client is limited in hip IR as well, working both simultaneously can allow the pelvis to tilt forward a bit better compared to just stretching the hamstrings alone. Sometimes proximal mobility will influence more distal mobility, sometimes it works the other way around, sometimes they don’t have any symbiotic relationship at all. The point is everyone needs to trial things for themselves and see the effect it has on their own body. If training hip IR or ER has no effect on their more functional ranges like a toe touch or deep squat, then don’t waste time with it for now.

Closing thoughts

There are no pre- requisites to move and when working toward your fitness goals. If that means improving lower body strength, endurance, or mobility- then there is an entry point at any and all levels. You don’t need to get your hip IR to any specific number before learning to squat. There is a ton of low hanging fruit to take advantage of before blaming your weak and awkward squat on poor mobility. You can choose more front loaded variations, box squat, use heel elevation, and adjust your stance to make the squat as comfortable and efficient as possible. Understanding proper bracing and pressure through the foot helps as well.

If you want to have a certain aesthetic with your squat and be able to squat ass to crass without any heel elevation or weight held in front to counter balance- then generally speaking, you may need some degree of IR. Im more interested in the ability to choose how I want to squat. I want to be able to sit in a resting squat, perform deep single leg squat variations, or demonstrate stable positioning when training for strength. I don’t want to be bound to only having the ability to train in one fashion long term.

Hip IR Is also tough to see noticeable changes. It requires dedication and potentially sacrificing other fitness goals to really unlock the hips. Sometimes that sacrifice is worth it for the individual depending on their long term goals or current pain/mobility levels. We shouldn’t make blanket statements on what form of training is relevant or useful without knowing goals. We don’t NEED hip IR to be healthy and move well. We also don’t NEED to squat heavy to be healthy and move well. We also shouldn’t need to obsess over very minor details within the movement/ health/ fitness space… But I like to nerd out on this stuff anyways.

What do you think? Is hip Internal rotation important for squatting? Have you found it beneficial for enhancing performance, mobility, or decreasing pain? or was it a complete waste of time for you?

Let me know your experience.

Thank you for reading!

Stay Supple,

G$